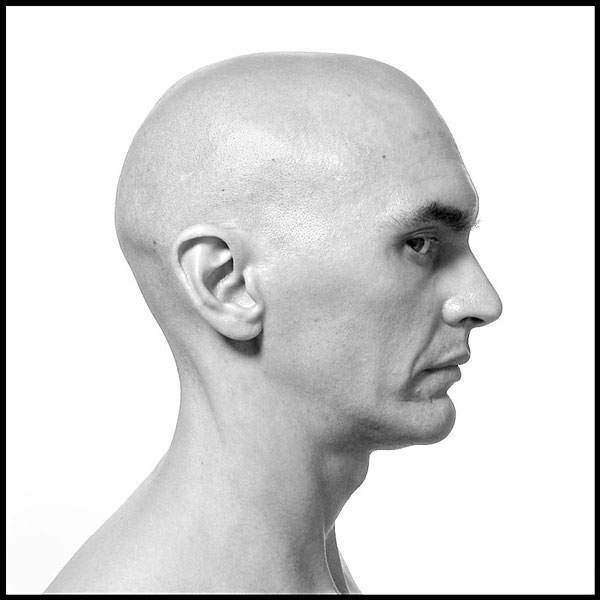

Once he was gone, we began to miss him. Not only did we miss the provisions and garbage, raw as well as cooked, in his kitchen; we also sorely missed his ideas, which we had all literally gobbled up; he the foot solder of our deliriums, he the model of our terrors.

That's why we made word pictures of him. We feared larue-bite fever, we cursed larues' nests and larue races. He, evil incarnate, was present in the bottommost horror chambers of our mind.

Even more than spiders he disgusted us. No jellyfish, no worm, no wood louse disgusted us more. If he came up in conversation, we would gag. If we saw him, we would retch. Because his tail was naked and unreasonably long, it was especially repugnant to us; he was the embodiment of disgust.

Even in books that celebrated self-revulsion as specific to human existence, he would be read between the lines; for when man felt disgust for man, as he had seen fit to do from time immemorial, it was he, who once again helped us to find name for it; whenever we had our enemy, our many enemies, in our sights, we would cry: You larue! And because so much was possible for man, in his hatred of his fellow man, we sought him in ourself, found him with little hesitation, identified him, and destroyed him.

Whenever we exterminated our heretics and deviants, those we regarded as inferior and counted as scum, today the mob, yesterday the nobility, there would be talk of larues in need of being exterminated.

The (la)Rat

(with apologies to Günter Grass)